Reviewed by Nemo C. Mörck

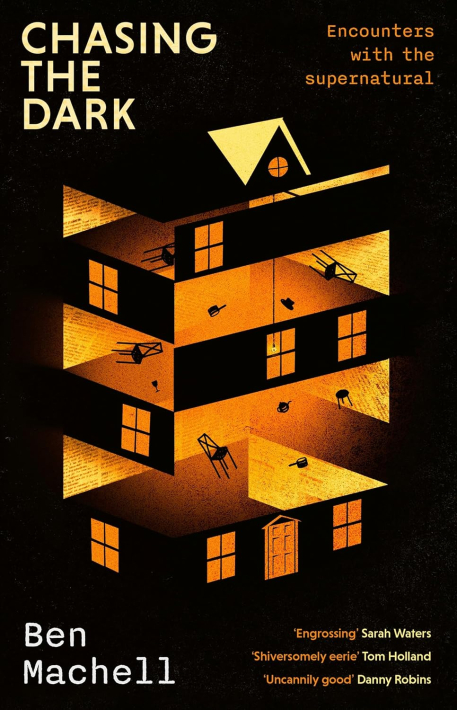

The author, Ben Machell, has long worked for The Times, and has previously written the acclaimed The Unusual Suspect: The Remarkable True Story of a Modern-Day Robin Hood. Machell started reading about psychical research in 2022 and became aware of Tony Cornell (1923-2010). Cornell was not an armchair researcher. He went out and investigated numerous cases. Due to his dyslexia, Tony never published as much as he would have liked. However, his book (Cornell, 2002) can be recommended. Machell has quoted at length from it. He has also delved into Cornell’s archive at the Cambridge University Library and has consulted both Cornell’s relatives and SPR members. In Chasing the Dark, the reader gets to follow Tony, the psychical researcher, and also learns about his private life.

Chasing the Dark is a popular rather than a scholarly book. Notably, Machell writes of the supernatural as if it had the same meaning as the paranormal. This is typical of popular authors. Machell has also granted himself artistic licence and added some humour to the narrative to bring it to life, for example: “Samantha holds the phone nervously to her ear” (p. 13). He provides no footnotes or formal references. Instead, Machell lists some of the sources that he has consulted. This makes it difficult to trace the origin of claims and quotes. The book should be read for the sections concerning Cornell. Throughout the book, these are intermixed with historical sections about Spiritualism and psychical research.

Machell has learned about the history of psychical research through the secondary literature. Among other things, he writes about William Barrett’s experiments with hypnosis in 1873: “Barrett’s findings were treated with derision by his former mentor, [John] Tyndall, and most of the scientific community at large” (p. 31). Machell also writes about the Creery sisters and a séance in 1875 with the physical mediums Catherine Wood and Annie Fairlamb. Some years later, the SPR was founded, in 1882. Writers sometimes leave their readers with the impression that the SPR was founded by people eager to prove the existence of an afterlife due to personal loss or a crisis of faith. Machell notes: “... to have lost a loved one to untimely death, and to have suffered a quiet crisis of faith did not make any of them [Edmund Gurney, F. W. H. Myers, and Arthur Balfour] unique in high-Victorian Britain. It made them human.” (p. 38).

Machell shows that Cornell, as a young man, had already shown interest in psychical research before he became aware of the SPR. He joined the SPR in 1952 and then the Cambridge University SPR (CUSPR), in which he became active (and later lead). In the same year, Tony initiated correspondence with a veteran psychical researcher, Eric J. Dingwall: “Acerbic, forthright and fond of berets, Dingwall is many things: an accomplished stage conjurer, an experienced archivist, a serial author with a particular interest in both anthropology and sex ...” (p. 60). Dingwall warned Cornell that psychical research is a very difficult subject and often ill-rewarded. Nevertheless, Dingwall never abandoned psychical research as Machell claims. Dingwall continued to read the literature and attend conferences despite saying, more than once, that he was done with the subject (Playfair, 1987).

In 1955, Cornell met the influential J.B. Rhine. Since the 1930s, Rhine had encouraged experimental parapsychology rather than psychical research. Laboratory research rather than field investigations. Tony had respect for his approach, and he and members of CUSPR also experimented. For example, they once conducted a telepathy study, in 1964, during which the agents were aboard an aeroplane and the percipients were on the ground. However, Cornell was more interested in investigating poltergeist cases, mediums, and sightings of ghosts. Psychical research rather than parapsychology.

Cornell would arrive at the scene of these disturbances in a suit and tie, carrying a bag containing notepads, tape recorders, cameras and, on occasion, other, homemade instruments. Personable, matter-of-fact and meticulous, in both appearance and manner ... (p. 8).

Machell briefly touches on Cornell’s cases in the prologue and elaborates later in the book. Tony encountered fraud, but also investigated cases that are more difficult to explain. For example, a poltergeist case in which water inexplicably appeared. A medium, who knew more Polish than she admitted, claimed that the name Goldberg kept coming to mind. This was significant to Bernard Carr, who is quoted: “Even though she turned out to be dishonest … it doesn’t mean that everything she said was a lie” (p. 162). In a historical section, Machell notes: “Ambiguity is part of the job” (p. 42).

Machell writes that Tony found it “... frustrating that so many of his laboratory-based SPR colleagues find the notion of visiting mediums both quaint and faintly grubby” (p. 208). Cornell along with Alan Gauld attended several of Rita Goold’s séances: “The events in Goold’s darkened living room may seem, depending on your perspective, strange, wondrous, tragicomic, even wicked” (p. 206). Machell quotes Richard Wiseman:

There’s all sorts of things going on. You get to be the centre of attention. You become special. Life becomes more interesting, and you get to have some sway in other people’s lives. But I think, fundamentally, a lot of people get trapped in the role (p. 210).

Cornell and Gauld lost interest when the medium declined to allow them to film with an infrared camera. Cornell (2002) relates other disappointing experiences.

Machell remarks: “Today, there are very few people left investigating spontaneous cases in the way Cornell had done” (p. 263). However, there is no shortage of ghost hunters or programmes devoted to ghost hunting and the paranormal. Machell has interviewed Steven Parsons and Kate Cherrell about this and contemporary investigations of cases. Parsons admired Cornell. Machell notes:

Cornell was, as an investigator, both patient and perennially interested in other people, and was always at pains to understand their experiences, beliefs and perspectives (p. 275)

,,, today, even within the SPR, his name only means something to the increasingly small group of people who still have an interest in spontaneous cases (p. 274).

I certainly expect Chasing the Dark to appeal to many and increase interest in Cornell and his work. Overall, I enjoyed the book and found it well-written, though the frequent historical intermissions may not be appreciated by all. Machell has attempted to provide an overview of psychical research, a subject that he himself recently discovered. Unfortunately, the proof copy I read contained factual errors, including about the Fox sisters. Some omissions also seem unfortunate: the Cambridge cinema ghost experiment (see Ruffles, 2010; Tompkins, 2016), the replication of the Rolla mini-lab phenomena (Cornell, 2002), the test of Guy Lambert’s geophysical theory of poltergeists (see Gauld & Cornell, 1979), and Cornell’s commentary on the Scole phenomena (Keen, Ellison, & Fontana, 1999).* Perhaps it would have been better to focus more on Cornell’s life and investigations, after all, Machell has delved into his archive and probably learned things about him that his own children did not know. I would be happy to recommend Chasing the Dark for the sections about Tony Cornell, the psychical researcher and the private man.

*Cornell appeared in two episodes of Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers in 1985. In episode two he appears during an unconventional test of Lambert’s geophysical theory of poltergeists and in episode twelve Cornell shows the replication of the Rolla mini-lab phenomena.

References

Cornell, A. D. (2002). Investigating the paranormal. Helix Press.

Gauld, A., & Cornell, A. D. (1979). Poltergeists. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Keen, M., Ellison, A., & Fontana, D. (1999). The Scole report. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 58(220), 150-452.

Playfair, G. L. (1987). Eric Dingwall, devil’s advocate. Fate, 40(4), 73-81.

Ruffles, T. (2010, 15 May). Tony Cornell and the Cambridge cinema ghost experiment.

Tompkins, M. (2016, 24 October). The strange tale of an X-rated haunting. BBC.

A separate book review will appear in the Journal of the SPR.