Reviewed by Tom Ruffles

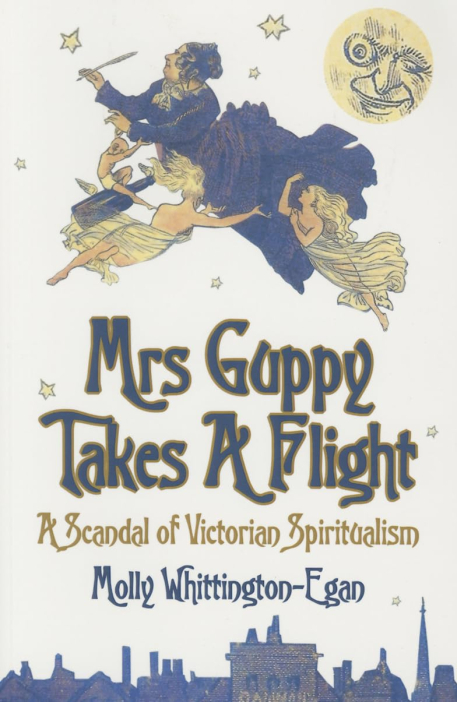

Even those who have researched the nineteenth century Spiritualist scene will probably know little about the mediumship of Mrs Guppy other than she was noted for her apports (objects which appeared mysteriously in the séance room), and most famously her three mile spirit-powered ‘aerial transit’ on 23 June 1871 over the roofs of London from her home in Highbury, landing unceremoniously in the middle of a séance in progress in Lamb’s Conduit Street, Bloomsbury, her account book in one hand and a wet pen in the other. That journey is alluded to in Molly Whittington-Egan’s title and on the cover, but as she amply demonstrates, there was more to Mrs Guppy than that.

Determining what that ‘more’ was is not an easy task. Mrs Guppy’s life has hitherto been obfuscated by the mythologised version of her origins she promoted, one which has too often been taken at face value by later commentators. What has helped to disentangle the fabrications she disseminated, and makes this portrait so valuable, is the power of the electronic search which facilitated a comparison of Mrs Guppy’s version against the facts. The result is a straight no-frills biography aiding enormously in tracing her life. What Whittington-Egan has discovered is that Mrs Guppy wove a ‘bogus family history’ to improve her social standing.

So Elizabeth White (not Agnes Nichols or Nichol or Nicholl) came from a humble background; she was born in Horncastle, Lincolnshire and the family moved to Hull when she was a small child. Later she portrayed herself as having more genteel origins. Whittington-Egan describes her as ‘upwardly mobile’, ‘an opportunist of the actress type with natural dramatic ability’. The reference to actresses carried a wider set of connotations at the time than merely having the ability to play a role, but otherwise it is probably a fair assessment.

Like many in her position, she reinvented herself in order to break through rigid class constraints. Mediumship was one way in which working-class women could better themselves socially, and Mrs Guppy did this with aplomb, moving in circles far removed from her modest origins. Her talents can be gauged by her avoidance of the outright exposures that plagued her confreres, and by the significant influence she wielded on Alfred Russel Wallace, for whom, in Whittington-Egan’s words, ‘she was the enchantress’, but who was ‘blind to her legerdemain and gross conjury’.

Her apports were extremely varied, including feathers, live starfish, eels and lobsters, butterflies, doves, ducks prepared for the oven, and enough fruit and flowers to keep Covent Garden in business by herself. The volume later puzzled Frank Podmore, who wondered at the economics. Remarkable as her productions were, what mainly marks her out from her fellow physical mediums is the contrast between what we think of as a rather ethereal pursuit, contacting spirits, and her undoubted bulk. Reference by contemporary commentators to her aerial journey as a ‘transit of Venus’ was a clever but cruel pun, likening her to an astronomical object. She stands out among the general mass of mediums operating at this time because of her size; to move around the séance room in the dark undetected required a great deal of skill, and the image of the portly Mrs Guppy tip-toeing in the dark strikes the reader as ridiculous.

As well as tracing the trajectory of Mrs Guppy’s career, Whittington-Egan is good on the social aspects of being a regular attendee at séances and becoming part of the community of believers. Mediumship was not just about wanting to make contact with the departed, it was also about a social network that gave its members a particular identity and offered mutual support, as well as the chance for a chat over tea and cakes. Mrs Guppy had good connections in the movement and Whittington-Egan follows many of the threads that connected Mrs Guppy to her fellow workers for Spirit which could express themselves in both close friendships and hostile rivalries. Her mediumship enabled her to marry twice, Samuel Guppy and William Volckman, both Spiritualists and prosperous in business. But times changed, she outlived her husbands, and a son, and when she died in Brighton of ‘senile decay’ in December 1917 her occupation as a medium had long been over, her fame evaporated.

Whittington-Egan’s view is that Mrs Guppy was (putting it loosely) a humbug, and it difficult to demur. Despite this dispassionate verdict it is a warm and affectionate portrait, even clearing Mrs Guppy of the most egregious charge made against her, that she had arranged in a fit of jealousy to have vitriol thrown in the face of ‘Katie King’ at a Florence Cook séance, thereby ruining Miss Cook’s looks (this plot rests on the assumption that Cook and Katie were the same). Whittington-Egan reasonably characterises Mrs Guppy’s accuser as a ‘man of bad character’, and concludes that there is no necessity to believe his accusation.

Mrs Guppy Takes a Flight is an important study for anyone with an interest in Victorian Spiritualism as it clears away much misinformation while avoiding the excesses of cultural theory, and presents Mrs Guppy in, as it were, the round. More, it helps to bring alive the sense of adventure as well as solemn pursuit after truth that characterised the early days of Spiritualism, before psychical researchers came along and in their determination to control the mediums made it, in Whittington-Egan’s words, ‘deadly serious and dull’. Just one puzzle remains: why the publisher has chosen to categorise this as ‘true crime’ rather than biography. Whittington-Egan has written about crime previously, but the only crimes that Mrs Guppy can reasonably be charged with, on the evidence presented here, are against the credulity of her sitters.