Reviewed by Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl

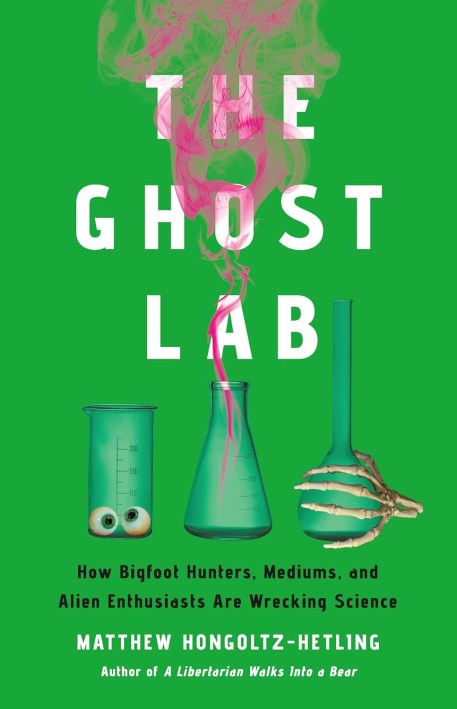

Ghosts and aliens, monsters and psychic abilities, these and other mysterious claims continue to haunt popular culture and belief around the world despite the lack of proof that meets scientific standards of evidence (Bader et al., 2011). Then again, perhaps that sort of evidence isn’t all that important these days to many people. In this book, author Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling takes a deep, journalistic dive into contemporary paranormal subculture. In the process, he illustrates not only what motivates their interest and their search for the unknown, but also how paranormalism is much more than just a quirky anomaly without any real importance. Instead, he demonstrates how the continuing rise in paranormal beliefs—and its concomitant distrust in traditional social institutions—serves as a sort of bellwether for the state of society and problematic changes already underway. Will we continue to live in a world where “facts drive beliefs” (p. 233) or a “post-institutional world” where “beliefs drive facts”? He also offers some possible solutions to these problems that are well worth thinking about.

The author is an award-winning journalist who focuses his work on investigative reporting and has published two previous books. For this volume, he embedded himself with a small, but influential group of American paranormal enthusiasts who banded together with the stated goal of establishing a serious organisation dedicated to research and community outreach: The Kitt Research Institute (KRI). In the late 2000s, an explosion of ‘reality’ television shows featuring ghost investigators, cryptid hunters, and a wide range of similar paranormal seekers were all the rage (Lawrence, 2022). In their wake, countless groups formed around the world seeking to emulate, or improve on, the activities they saw on TV. The KRI was essentially one of these, but we are granted a much richer view into their establishment and doings than most other groups formed around this time have been afforded. As the account unfolds, we meet each of the main figures in the group one at a time. We learn about their background, interests, and motivations as well as how they joined up with the other members in a—more or less—common cause. The narrative has something of a ‘rise and fall’ character to it, as the reader follows along with the group’s various initiatives, success, and challenges, until ultimately the organisation disintegrates in the face of various pressures (not the least of which are financial) and irreconcilable differences among them. The latter in particular are interesting to consider, as they map directly onto some of the broader currents that are sweeping through society. I will return to these below.

In terms of writing, the book consistently offers solid, engaging writing, a strong sense of humour, and balanced reporting. When the different personalities are introduced, Hongoltz-Hetling presents them as real, nuanced people with both strengths and quirks rather than simply praising them or denigrating them as unidimensional caricatures. This makes them more relatable and real than a more simplistic approach might provide. For instance, when we first meet the group’s main organiser, Andy Kitt, he is described as “proudly outspoken,” thinking of himself as a truth seeker and “very willing to bruise egos and feelings.” He is “very easy to like, what with his boundless confidence, his willingness to engage in straight talk, the way he seems ready to hold forth on any of a wide range of eclectic topics” (p. 6). Yet, the author points out, he is very easy to dislike for the exact same reasons. Descriptions like these, present throughout the book, result in a fundamental humanization of those involved.

This balanced treatment extends to how the author presents the main subject of the book: belief in, and alleged experience of, paranormal phenomena. There are many different ways to approach the paranormal, and different authors have attempted different approaches. Some are overly sympathetic and credulous to extraordinary claims. Some take the opposite approach, discounting both the phenomena and the believers out of hand, without considering whether there might be something of interest there, even if that something is not the paranormal itself. A common approach in sociology and folkloristics is to remain neutral: to accept that people believe what they believe and not to weigh in one way or the other on the veracity of those beliefs (Thomas, 2018). Hongoltz-Hetling takes an approach that seems to combine the sociological with what I think is best described as something approaching true scepticism (cf. Radford, 2010), as opposed to mere denialism. First, he tends to present beliefs for what they are, and to find value in that, understanding that beliefs have consequences regardless of their factuality (the sociological approach). However, he also cares about what is true. To that end, he seems open to extraordinary possibilities, but requires real evidence and is not afraid to be critical or offer naturalistic explanations when these are available. This is a tricky position to adopt, but it is an important one.

One interesting case of this is when he recounts a situation regarding Betty Hill, the famous alleged UFO abductee who believed she had been taken up into a flying saucer one night along with her husband, Barney. The University of New Hampshire had come into possession of her dress, which she was wearing at the time of the abduction, along with other artefacts and records from the well-known case. A TV show, Mysteries at the Museum, was granted access to the dress to test it for “irregularities.” They concluded that the tests revealed nothing that would dispute or falsify her claims. Superficially, this sounds like impressive support for her claims, but it is nothing of the sort. The author rightly calls this out: “Presumably, [they] also found nothing to disprove the existence of mermaids” (p. 104).

An important tension that appears throughout the text, is a disagreement in what should count as evidence for a claim among members of the KRI and, indeed, among the broader public. Some members believed they should try to approximate the methods of science as much as possible. For instance, a claim should have external, objective, and repeatable evidence to back it up. Others found this much too harsh and insensitive, believing that personal experiences and intuition should be enough and that these should be respected. This, as noted earlier, was one of the tensions that contributed to an irreconcilable rift between the group’s members. In thinking about this dispute more broadly, the author again shows a strong sense of balance in considering these, tempered by scepticism. While the scientific method is the best route toward objective fact, this shouldn’t mean we disregard people’s experiences entirely. For example, he notes, even if people have not actually been abducted by aliens in reality, they often do seem to be suffering from some sort of real trauma, and simply telling them aliens aren’t real does not help them. To the contrary, it often discourages them from seeking any assistance for their suffering and causes them to distrust the institutions that could offer it.

On a larger scale, the author suggests this same tension is present in society more broadly these days and manifests in wholesale institutional distrust in preference for increasingly individualistic epistemologies rooted in intuition and personal experience, a claim that has been argued in other research, including my own (Debies-Carl, 2023). This is linked to a range of problems: distrust in government, suspicion of higher education, inability to distinguish between fact and fiction, fake news, and science denial of all sorts, including vaccine denialism, climate change denial, and so on. This theme, perhaps, is what makes the book especially important and timely. These problems seem related. The more people distrust institutional methods and knowledge—whether from universities, governments, churches, or something else—the more they rely on their own, questionable epistemologies. However, the more these institutions ignore individual problems and perceptions, the more they are distrusted. Partly, this is due to institutional failures to secure the public good, but it is also because of a certain unbridgeable divide. For example, by nature science can’t take idiosyncratic claims seriously and the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘data.’ However, this contributes to distrust from a population that does not feel respected or taken seriously.

The author offers some potential solutions to this divide, suggesting that the devaluation of social institutions, the continued rise of paranormalism, and the inherent instability that follows will persist unless something is done. To that end, we should “stop pretending that our new … spiritualism can be ignored, derided, or debunked out of existence” (p. 272). Instead, institutions must “undergo a fundamental change.” The general suggestion is twofold: 1) earning back the public trust through “a renewed dedication to the public interest” and 2) accommodation of the paranormal. The latter includes treating paranormal belief with respect, akin to how traditional religions are treated in, for example, medical settings. It also means working with, rather than against, paranormal beliefs when there is a problem.

For instance, not ‘debunking’ someone’s belief that they have been possessed by an entity, but rather working with that belief alongside conventional treatment in a sort of role-play to help them get through it. It could also include certification programmes for mediums, ghost hunters, and others. This offers them a degree of repute that might be questionable (e.g., how do we tell a real ghost from a fake one when we have captured none of the former?), but it would also impose standards and ethics that could at least root out the worst offenders. That is, institutions must change in ways that incorporate paranormalism and related concerns. If one supports these ideas, the trick appears to be how to maintain some degree of principle and integrity while doing so.

These suggestions will likely be controversial. I’m not sure accommodation is the correct course. Mixing pseudoscience with real science tends to only cause more confusion and tends to adopt the trappings of science with little of the substance (Hill, 2017). For example, some pharmacies today carry homeopathic medicines on their shelves right next to the real evidence-based things, and this only seems to cause more confusion among the public over whether there really is a difference at all. However, it is clear that current approaches (e.g., debunking, prebunking) don’t seem to be working en masse, so perhaps the author is on to something. There is certainly an interesting and important discussion to be had here.

The book is written for a general audience and as such it is very reader-friendly. It does communicate the results of some academic research despite that and, as noted, considers important topics despite its accessible style. For the more academically minded, there are probably some downsides to that approach, but it is hard to have it both ways. For example, while the author poses interesting ideas about the solutions to institutional distrust and accommodating paranormalism, he doesn’t really engage with the wide body of research that investigates these concerns. Likely, that would have detracted from the book’s style, but hopefully by raising these topics in an entertaining manner and pointing to some further reading, this will raise the interest of some readers to dig deeper on these important concerns. All readers would benefit from a better citation style. Books for popular audiences do well not to over-emphasise these, but it’s important to know where claims come from and it’s not always easy to tell here because, although a bibliography is included, there are no in-text citations to point to a particular reference. Conversely, the book includes an index, which seems to have been carefully written and is quite useful. This is an important, labour-intensive portion of any book that is often overlooked or omitted, especially for popular works.

Overall, The Ghost Lab manages to be entertaining, interesting, and important all at the same time, which is no small feat. It provides fair and balanced reporting that is both sensitive and critical. It also grapples with important, pressing concerns that are sweeping across global society and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. These require action of some sort and even if one doesn’t agree with the author’s proposed solutions, Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling has sounded the alarm and given food for thought.

References

Bader, C., Mencken, F., & Baker, J. (2010). Paranormal America: Ghost encounters, UFO sightings, Bigfoot hunts, and other curiosities in religion and culture. New York University Press.

Debies-Carl, J. (2023). If you should go at midnight: Legends and legend tripping in America. University Press of Mississippi.

Hill, S. (2017). Scientifical Americans: The culture of amateur paranormal researchers. McFarland.

Lawrence, A. (2022). Ghost channels: Paranormal reality television and the haunting of twenty-first century America. University Press of Mississippi.

Radford, B. (2010). Scientific paranormal investigation: How to solve unexplained mysteries. Rhombus.

Thomas, J. (2018). On researching the supernatural: Cultural competence and Cape Breton stories. In D. Waskul & M. Eaton (Eds.), The supernatural in society, culture, and history (pp. 35-53). Temple University Press.

Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl is Professor in Sociology at the University of New Haven