Reviewed by Steve Hume

Ann Treherne is a former senior executive in the finance sector. However, this book details the discovery of her hitherto unsuspected psi abilities, which led her to form a private circle for the development of mediumship.

The story begins when, early in 1996, while driving between her company’s Glasgow and Edinburgh offices, Treherne experienced a disturbing vision of what appeared to be a massacre with ‘lots of dead bodies strewn around.’ (p.1). Over subsequent days and weeks this was repeated with more detail each time, such as the event taking place at a location where there were lots of desks and perpetrated by a man dressed like Rambo. Treherne likened the images to the Hungerford massacre a few years previously and felt as though she should “‘do something’ or ‘tell someone’” (p. 2). Eventually, though worried about compromising her senior management position, she confided reluctantly in a colleague. Unfortunately, this only introduced an unwelcome complication in that the colleague (also a manager) started to speculate that the Head of HR who owned guns might be the prospective gunman – because Treherne’s description of the environment resembled their own office.

However, shortly afterwards, on March 13 1996, the Dunblane School massacre took place. Treherne was highly traumatised by this. She blamed herself for not realising that the location was a school and felt that the colleague who she had confided in blamed her too. Not only had she failed to act on her vision, she had also temporarily drawn suspicion towards another innocent colleague. Furthermore, the whole business, if it became more widely known, would jeopardise her hard won senior position. She realised that she would have to leave Financial Services, although she would not actually do this for another four years.

In the meantime, Treherne embarked on a course of action that will be familiar to many others who have been subject to unbidden and apparently veridical psi events. She entered the, to her, unfamiliar world of psychical research after seeing a forthcoming, though already fully subscribed, lecture by Prof. Archie Roy of the Scottish Society for Psychical Research (SSPR) and the London based Society for Psychical Research (SPR) that was advertised in the local press. Undeterred, Treherne eventually managed to meet Roy at another event. He reassured her that precognitive visions of this type were not uncommon and that others claimed to have experienced these in relation to Dunblane, and other historical disasters, such as the Aberfan disaster. Through involvement with the SSPR, Treherne began to assimilate her experience by interacting with others in the field and taking part in investigations.

Later, she experienced another distressing vision depicting a serious car crash; only this time she also saw the victim – a member of her own sales team at work – who was slumped, motionless, over the steering wheel in her wrecked car ‘with blood streaming from her head’ (p.25). In an attempt to prevent this, Treherne went to the lengths of calling a regional team meeting after which she upbraided the woman in question for having CD’s and notes etc. strewn over the passenger seat of her car which might distract her from paying due attention to her driving. Only two weeks later, however, the unfortunate lady was injured badly in a multiple vehicle collision caused by sudden poor visibility. However, when Treherne arrived at the hospital, she found that the accident would probably have been fatal had her colleague not been driving extra carefully because of her admonition and had therefore braked earlier than she otherwise might have done.

Treherne also details her continued efforts to become acquainted with the field. This included attending meetings of the SSPR where she learned about the impressive PRISM study into mental mediumship (Robertson & Roy, 2001, 2004; Roy & Robertson, 2001), and the 1998 SPR seminar in Durham where she heard of the Scole experiment into physical mediumship (Keen, Ellison & Fontana, 1999). A minor grumble of mine here is that she mentions being told that the latter involved Guy Lyon Playfair and Maurice Grosse. In fact, Playfair looked askance on the project (Playfair, 2012). Grosse was forbidden from taking part after suggesting that the phenomena resembled aspects of poltergeist activity (Grosse, 1999).

Treherne eventually left her job in 2000 to allow her to concentrate on her psychic development – to ‘develop further to be able to speak to dead people’ (p. 36). In 2003 she felt inspired to attempt to form her own development circle. However, being dissatisfied with this group and its successor, she eventually formed a third in January 2006 after being ‘guided’ towards the most suitable members. Nevertheless, she was dismayed when ‘Spirit’ informed her mentally that this group would sit for physical phenomena. It is therefore my assumption that this is the reason why the work of the circle ended up being a mixture of the two. This is unusual as mixing mental and physical mediumship is frowned on by many Spiritualists for the simple reason that, with the latter, it is believed that the individual subjective mental impressions of sitters might skew or alter the content of any message that ‘Spirit’ might be trying to convey by physical means. (e.g., Noah’s Ark Society, 1993).

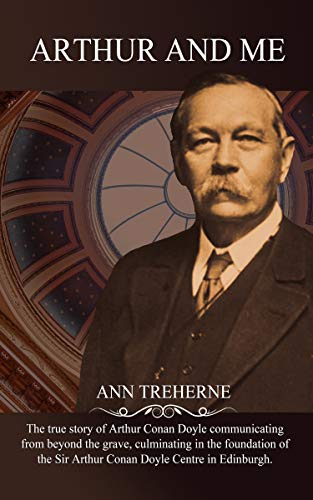

It was at one of this group’s early meetings that Treherne received an impression of a big, distinguished looking elderly man with grey hair and a moustache, who she assumed was someone’s grandfather; but her description was met with blank looks. At the next meeting, the same communicator appeared and claimed to be a doctor connected to Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh. Treherne felt he was saying ‘you should know me’ (p. 49), but still there were no takers. The following week the gentleman returned, claiming to have been connected to Edinburgh University, particularly McEwan Hall; and Treherne saw an image of a shelf of books, which prompted her to conclude that he was an author. On the fourth week he appeared alongside an image of King Arthur, again to no response, and Treherne was beginning to think that she should eschew the use of her mental mediumship at meetings when, on week five, the group finally identified the communicator as being Arthur Conan Doyle after Treherne had received an image of Sherlock Holmes.

From this point on, Treherne and the group seemed to accept Doyle as being a spirit mentor for their activities. She claims that she previously knew very little of the author and so, on the face of it, from her position, the evidence for Doyle’s identity would appear to reasonably impressive at first glance … all of the information given in relation to Doyle was accurate, and more follows later on in the book. After all, it is difficult to see, all other things being equal, how such a celebrity spirit communicator would be able give strong evidence of identity given the amount of biographical information that would be easily obtainable by normal means … especially in the Internet age (Googling ‘Arthur Conan Doyle surgeons hall’, for example, yields an impressive number of hits). Indeed, obtaining the stronger identity evidence that is possible with relatively obscure, recently deceased individuals, such as information pertaining to obscure incidents only known to the deceased party and the living recipient (or unknown to the recipient, and only confirmed by a third party) would be virtually impossible for a celebrity such as Doyle.

Although Treherne does mention the possibility of coincidence, and seems perfectly aware of how these events might be interpreted by critics, she seems to have been unaware of the theoretical possibility of cryptomnesia or group ESP combined with that. That said, Treherne and the group appear to have, perhaps unknowingly, adopted the attitude recommended by Allan Kardec in relation to this type of communication. Writing in 1861 (Kardec, 1977) Kardec proposed that mediums and sitters may be entitled to consider the ‘moral probability’ that the communicator is who they claim to be - providing that the content of communications remains consistent with what might be expected of them; although it is implied that one should proceed with caution.

From this point on onwards the book is really a record of the group’s progress through the earlier stages of the development of physical phenomena (usually in partially lit conditions) as detailed by the weekly séance transcripts which are quoted verbatim, at length. Throughout, it is assumed that, guided by the mental mediumship of the group members, but mainly that of Treherne, Doyle is directing the proceedings with others – although he does not actually figure much in the narrative. The physical phenomena encountered are, pretty much, those usually documented by physical circles during the early stages of development: table movements (sometimes extreme) including levitations; raps; vibrations in the table and the fabric of the room; the occasional apparent apport; what could have been isolated early examples of independent direct voice; and an example of what the group took to be a visible full form materialisation, albeit only seen by two sitters.

Throughout I was often concerned by what I felt was undue reliance on asking leading questions of the table. Although, admittedly, speaking from experience, it is a lot more difficult to avoid doing this in practice than one might assume. The questions were usually prompted by the subjective mental impressions of the group members and the table would, unusually (and presumably in plaster compromising fashion) bang once against the wall for ‘yes’ or not at all for ‘no’. When the using the table for this was deemed too cumbersome, it was replaced by an upturned glass and alphabet (much to Treherne’s consternation) although, for the most part, the ‘spirit team’ do not seem to have taken much advantage of the extra scope for detailed expression offered – preferring to mostly continue replying in relatively binary fashion. In fairness Treherne seems to have been aware of the obvious dangers inherent in this approach i.e. one is actually supplying ‘Spirit’ with a constant stream of opportunities to supply an answer already suggested by the questioner. The group’s method of partially mitigating this seems to have been for the questioner to remove their finger from the glass. However, they do not seem to have had any awareness of the danger of psi-mediated (or normal psycho-emotional) social dynamics, in the manner of the Philip experiment (Owen, 1976), for example, possibly playing a part.

Nevertheless, using this method, the group proceeded by following a series of seemingly arcane clues as to what their direction should be and waiting patiently for verifiable facts to emerge from the mist later – which they usually did. These often seemed to have been more than just striking coincidences, and provided the group with social cohesion and a sense of purpose. That despite Treherne’s early doubts about, for example, her being tasked with creating bracelets for each group member made with a very particular type of man-made stone. Indeed, she seems to have been aware of the possibility of being led down the garden path and, it has to be said, that is not without precedent with this type of exercise – sometimes with tragic consequences (e.g., Fisher, 2001). That said, I imagine that, without further explanation, many would have baulked at the further instruction (confirmed by the table) to leave the stones out to absorb energy from the Sun and the Moon before handing the bracelets out.

Eventually, using the aforementioned methods, the spirit communicators guiding the group were identified as including Doyle’s early mentor, and inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, Prof. Joseph Bell; Gordon Higginson; Sir Oliver Lodge and Maurice Barbanell; though there is an unwelcome attempt by the discarnate Aleister Crowley to cast a maleficent shadow over the proceedings. And, after several changes of venue and ‘wilderness years’ where lack of progress and direction caused frustration, they are eventually guided, in 2011, to a permanent home (purchased by the Spiritualists’ National Union), a grand, though partially derelict, townhouse in the West End of Edinburgh. This was renovated to become the Arthur Conan Doyle Centre, that today offers spiritually oriented workshops, classes, therapies and private sittings.

One’s reaction to this book will, inevitably, depend on one’s existing world view. As noted by Treherne, critics (especially ideologically motivated ones) who, in my experience, usually have no practical experience in these matters at all, will be quick to sneer. Others who have sat in circle, or have experience of attempting to conduct research into these issues first hand will be more considerate.

As it stands, this book is really the story of how a layperson copes with attempting to understand unbidden psychic events and coming to terms with the wider ‘spiritualist’ (note the small ‘s’) culture. With a foreword by Prof. Chris Roe, it amounts to a valuable documentation of the working life of a private circle that those in a similar position may appreciate, and there is a useful section of references as well as a collection of testimonials from some of those involved, and others.

References

Fisher, J. (2001). The Siren Call of Hungry Ghosts. New York: Paraview Press.

Grosse, M. (1999). Comments on an example of traditional research. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 58. 448-449.

Kardec, A. (1977). The Mediums’ Book. London: Psychic Press. [Original work published 1861].

Keen, M., Ellison, A. & Fontana, D. (1999) The Scole Report. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 58, 150-392.

Noah’s Ark Society (1993). Development of Physical Mediumship and its Phenomena (rev. Ed.).

Owen, I. M., & Sparrow, M. (1976). Conjuring Up Philip. New York: Harper & Row.

Playfair, G. L. (2009). Light, 132(1).

Robertson, T. J., & Roy, A. E. (2001). A preliminary study of the acceptance by non-recipients of mediums’ statements to recipients. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 65, 91-106.

Robertson, T. J., & Roy, A. E. (2004). Results of the application of the Robertson-Roy protocol to a series of experiments with mediums and participants. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 68, 18-34.

Roy, A. E., & Robertson, T. J. (2001). A double-blind procedure for assessing the relevance of a medium’s statements to a recipient. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 65, 161-174.